In a prior post on The Evolution of an Asset Class (The Current State of Private Equity), we covered the recent trends in private equity over the past ten years and its current impact on the SMB market. In this post, we will look back even further, looking at how and why General Partnerships have evolved.

I want you to re-frame PE funds as small and medium-sized businesses that provide a service (returns) to their customers (investors). The vast majority of PE Funds had one strategy (product). This product concentration also had key-person risk and cycle risk. Combine all of this with the term “leveraged buy-out” and you have a high-risk / high-reward investment strategy.

GPs and LPs were aligned - carried interest - is the carrot. Low equity contributions (<25%) and high corporate tax rates made it feasible to take on onerous amounts of debt. An unregulated debt market (re: junk-bond boom) combined with lower multiples also contributed to the highly-leveraged buyout. For example, the take-private of Jerrico (owner of the franchisor, Long John Silver’s) for $620 million in 1989 requires less than 5% equity contribution.

Now, back to the entrepreneurial founders of PE funds. While they were focused on investing in growing businesses with structural barriers to competition, most were not looking in the mirror. The funds mostly took a generalist approach, with few specialists - they were relatively undifferentiated.

The founders of these funds built a strong business that generated extensive wealth for all of their partners. However, the names on the door held onto most of the carry pool, and talent spun out in search of greener pastures. The firms did not have much “value" if they were put up for sale by an investment bank, and thus “partner” buy-outs and generational succession plans become increasingly important. These pure capitalists, while motivated by legacy, still wanted to hold onto economics, despite no longer being in “the game”.

While many firms faced this conundrum, some decided to minimize “key-person risk” and “product concentration” by expanding and diversifying their fund strategies into adjacent areas and services. For larger funds, it was often creating a middle-market strategy, filling the void where the firm had historical success. Larger funds expanded into new geographies (e.g., Europe, Asia, Australia). Funds also created credit vehicles (e.g., BDCs, Mezz Funds, CLOs), while some moved into entirely different asset classes (e.g., Real Estate, Commodities, Hedge Funds). This had the benefit of increasing the number of revenue-generating products for GPs, mitigated strategy risk, and enabled cross-sell of an existing customer base (institutional LPs).

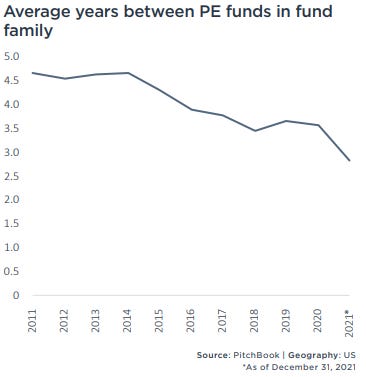

By transitioning their single-strategy funds into institutional firms, these SMBs began to scale into real businesses (asset managers). The primary risk at this point shifted to their ability to generate returns - the cost of failure became high. As a result, GPs began to shift away from maximizing leverage in deals, as the cost of failure became high. This allowed them to over-equitize deals, deploy capital more quickly, and raise funds over shorter time frames.

The impact on the investment approach is reflected in the current state of the market. Instead of buying low-growth businesses with perceived moats by maximizing leverage, asset managers transitioned into acquiring high-growth businesses with large addressable markets. While this strategy reduced risk, it allowed management fees to balloon. Per BCG’s Global Asset Management Report (2021), alternatives represented ~15% of AUM but generated ~42% of revenue, not inclusive of performance fees. As of 2003, those numbers were ~9% and ~27%, respectively.

The customer base (LPs) for alternatives can be summarized into Pension Funds, Non-Profits, Retirement Plans, Family Offices, and High Net Worth Individuals. Pensions are the largest investor pool - and their need to shift towards alternatives has been driven by a funding deficit and the need for higher returns. A good amount of these customers, including pensions, use third-party consulting firms and RIAs for asset allocation and manager recommendations. Now, put yourself in the shoes of a third party recommending one of your biggest clients to allocate capital on behalf of firefighters and schoolteachers. Are you going to recommend the established incumbent or the unproven upstart? The cost of failure to back an upstart is not worth it - you’d recommend the incumbent. This dynamic has only served to multiply the capital base of large asset managers.

As the industry transitioned from a fund approach focused on “hunting” companies to acquire to asset “gathering,” the focus became more on generating management fees than carry. When you think of management fees, they are an extremely attractive revenue stream. First, they have long-term visibility (five-plus years). Second, capital scales, and there is a high degree of operating leverage as successor funds increase in size. Think of another industry with high-recurring revenue, operating leverage, strong unit economics, and a massive, underpenetrated TAM - software.

In the next newsletter, we’ll dig deeper into the SaaS comparison. In subsequent versions of The Evolution of An Asset Class, we will cover other instruments that helped create and push forward the asset class as it continues to mature. These topics include secondary markets for LP interests, fund of fund, GP seeding, GP staking, and single-asset continuation vehicles.

Once we’ve covered the past, we will begin to look forward. If you are familiar with the term “solo-capitalists,” which was coined by Nikhil Basu Trivedi, and the current trends in the SMB PE market - the lower middle market of private equity is poised for disruption.

Please share this post with anyone you think may be interested. Thanks for reading.

VAC